My Story

by Lang Elliott (1500 words)

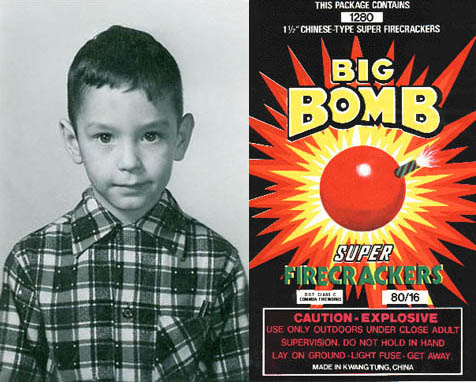

You may be wondering why and how the Hear Birds Again project has come into being. In brief, it is the endpoint of a long and arduous personal journey that was born of necessity, in the aftermath of violence. When I was about eight years old, I was in a firecracker accident where a “cherry bomb” exploded just above my head, greatly impairing my hearing in the high range.

My neighbor Skip and I were tossing cherry bombs up into an oak tree, lighting the fuses and timing our throws in an attempt to blow up a squirrel’s nest (bad, bad, bad). Skip ended up tossing one that hit a limb and bounced straight back. “Watch out!,” he yelled. I turned my head, but it was too late … KA-BOOM! … the cherry bomb exploded right on top my head (instant karma?) and my life was forever changed, though I did not realize it at the time.

At first, I couldn’t hear a thing, but after a few days my condition improved considerably, and I could hear humans speaking again. My parents hauled me to an audiologist who determined that I still had good word discrimination and did not need hearing aids. Thereafter I noticed that I could no longer hear the “ping” of a dime falling on the sidewalk, or the steamy hiss of water boiling on a stove, but that didn’t seem like a big deal. So I forged ahead, thinking my hearing was “pretty much okay,” at least in terms of sensing what seemed, at the time anyway, to be the important things in life.

All went smoothly until many years later when I became a graduate student at the University of Maryland, studying animal behavior. That’s when a chance event brought my hearing loss back into focus.

I had made friends with Gene Morton, an ornithologist specializing in avian communication. While accompanying Gene on a bird walk in late spring, Gene got very excited when he heard a Worm-eating Warbler sounding off in the distance. I didn’t hear it, so Gene led me to the tree in which the bird was perched, and the two of us watched intently as it sang from a limb no more than twenty feet away. Still, I could not hear its song. I was devastated. Watching the warbler open and close its beak in silence was an excruciating experience. All my imaginings of being a hear-all-see-all field biologist evaporated in that instant … oh, woe was me!

Although deeply disturbed about not being able to hear the warbler, I knew that its song was very high-pitched. And given that I had no trouble hearing robins and cardinals and blue jays, I was hopeful that I was still hearing “most” of what was happening in the bird world. Such a comforting thought, but just to be sure it was true, I decided to run a quick test.

It just so happened that I owned a Uher reel-to-reel tape recorder. With spring still going strong, I went into a seemingly quiet forest with my Uher and recorded for several minutes at the highest speed setting. Then I played the recording back at half-speed and quarter-speed, thereby slowing the playback and lowering the pitch accordingly. I was stunned at what I heard … LOTS of birds singing, most of which I could not hear at all when played at normal speed. In a complete state of shock, I could not help but let out a PRIMAL SCREAM.

Subsequently I had my hearing tested by an expert audiologist and discovered that while I had normal hearing to around 2500Hz, I had severe hearing loss above 3000Hz, so much impairment that conventional hearing aids would be of little help. While this was terrible news, there was sort of a silver lining.

I remember thinking: Hmmmm … if I can hear the high birds songs just fine when they are lowered in pitch (as I did with the tape recorder), then there must be a device that will do the pitch-lowering for me in real time, allowing me to hear the missing birds when I take walks outdoors.” So I searched high and low, only to discover that no such device existed. Aaargh! Depressing news for sure, but rather than resign myself to never hearing high-pitched birds, I became even more determined to find a solution.

Fortunately, while checking out products made for the music industry, I stumbled upon the Bode Frequency Shifter, a popular device invented by electronic genius Harald Bode. So, in 1977, I got in touch with Mr. Bode and soon contracted him to build a “bird song friendly” version of his device that I could use outdoors. And presto!, just a few months later, my one-of-a-kind Bode Bird Song Frequency Shifter was delivered to my doorstep and I was finally able to hear the high-pitched singers in real time during bird walks. O Frabjous Day, finally a solution! But as it turned out, perhaps not the best one …

My One-of-a-Kind Bode Bird Song Pitch Shifter.

Unfortunately, my Bode device was bulky and heavy, and the heterodyning method used for frequency shifting was far from optimal because it distorted frequency relationships within songs, making it very difficult to identify the singers. So I ended up rarely using it. “Surely,” I thought, “I can find an even better solution.” So I continued my quest.

About ten years later, shortly after moving to Ithaca, New York, I approached Herb Susmann, an electronic engineer freshly-minted from Cornell University. Herb found my project compelling and thought we could utilize miniature digital signal processors (DSPs) to perform the pitch-shifting in a way that would maintain frequency relationships. And Herb was right … in 1991 we gave birth to the SongFinder: A Digital Bird Song Hearing Device that elegantly shifted high-pitched bird songs by a factor of one-half, one-third, and one-quarter. Our device, which was well-received and much-loved by birders suffering from high frequency hearing loss, included a special binaural headset that not only allowed users to determine the distances and directions of high-pitched bird songs, but also locate and observe the singers.

Our First SongFinder

Our first SongFinder was considerably smaller and lighter than my Bode device, but still too large to fit in a shirt pocket. So, in the early 2000s, we incorporated new electronic components that made the SongFinder even smaller and more efficient, and in 2008 we improved the design once again, making the unit small enough to fit into a shirt pocket.

Lang with a SongFinder in 2013.

All Three SongFinder versions sitting atop the original Bode Frequency Shifter.

Herb and I continued selling the SongFinder until October of 2018, a 27 year run during which we sold about two thousand units. After nearly three decades of production, it was clear that we needed a more flexible, modern solution and that our frequency shifting approach should be manifested as an application for mobile phones. Thus, Herb and I brought SongFinder production to a close and I began looking more deeply at the possibility of creating an iOS app that would do the same thing, but do it better.

I soon approached Harold Mills, an experienced programmer who helped develop sound analysis software for the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Harold thought it was a great idea and suggested that we make it an open-source, non-profit project. I concurred and we agreed to work together to bring Hear Birds Again into being. Harold immediately went to work creating a working prototype of our app and I busied myself developing a support website and prototyping headset designs. We formally launched our project in November of 2021 and began raising funds. Almost exactly one year later, in early December of 2022, we published the first version of our app. Hallelujah!

Hear Birds Again is now available in Apple’s App Store!

For me, the release of Hear Birds Again marks a major milestone in my life. It’s been 46 years since Harold Bode built my first frequency shifter for bird songs, and it’s high time I got this idea out of my system and into the world, on a much larger scale than before. At the ripe age of 74, I am ready to hand this idea over to others who will hopefully devise even better ways to accomplish our goals. No, I’m not abandoning the project. I still intend to do whatever I can to help Hear Birds Again expand and evolve to better bring bird songs back to nature lovers the world over. In a real sense, this has been a “life’s calling” and I am incredibly pleased to see it finally cross the finish line.